No More Normal

From 2015:

I have a story to tell you. This is a story about a young family, leaving behind everything familiar and setting out on a harrowing journey, which forever altered the course of their lives. The year is 1969. The young father and mother, both 33 years old, have three children ranging in ages between nine and thirteen years old. They travel in their car up a one-lane dirt road, at night. It is mid spring, and still cold outside. The car is a station wagon, and the father is driving. The mother is sitting next to him and the three children are sitting in the back seat. The car is crunching over rocks, sticks and leaves as it travels up the road, heading toward a house full of strangers and a life of uncertainty.

The car is packed with blankets, clothes, and the few personal belongings they could fit. The middle child is 12, that’s me, Cheryl Lynne, painfully shy but sharply observant, mostly over-looked because I don’t make a fuss. My sister, Kay Anne, is 13 years old, she’s the extrovert, reveling in the attention she demands. Our brother, Paul, the adored baby of the family, is nine.

My grandfather nicknamed Paul ‘Boy.’ Rushing onto the plane after it landed in Los Angeles from Portland, Oregon, to grab his newborn grandson, his namesake, from my mother’s arms, shouting, “That’s my Boy! That’s my Boy!” My grandparents were from Texas, where family is everything, the only thing worth value. And it was my brother only, in 1972, that my father’s sister brought into her home; she cut his hair, bought him new clothes and enrolled him in a nearby school. After six months, my frantic mother ‘rescued’ her son from this home.

Our car is heading away from our home, away from the known and the beloved. The house had been packed up, some stuff thrown away, more stuff given away, and what couldn’t be parted with is stored in friends’ garages in the valley. Over the years, these belongings, like so much else, would disappear.

The headlights shine up into the darkness, showing the road and bathing the trunks of the trees lining the road in light. My father is telling jokes, laughing, singing, and trying to cheer up his stunned children. Suddenly my mother turns to the back and snaps at us, “Can’t you see how hard this is on your father?”

Good god, what? Was she kidding? I felt the shock go deep into my body, and bewildered by her anger I waited, but my father went silent. His silence was more disturbing to me than her angry outburst, for I had never known him to be at a loss for words.

The car continues climbing up to the top of the ridge, to the unfamiliar house, where my family will stay for a few weeks. This will be the first stop in a long line of other strange houses where we will stay for a few weeks, maybe a few months. I have no idea where we are going as we grind slowly up the road, just a vague notion of “staying with friends for a little while.” My father parks the car and we go inside with our small bags, the otherness of the place and the strangeness of the people make me hang back.

Our house, our home, nestled in the hills of Lagunitas and perched at the top of a small, winding road, had always been filled with love, books, and music. Famous musicians - Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead, John Cippolina and Jim Murray of the Quicksilver Messenger Service, Michael Bloomfield and many others - were always dropping by to jam with my father. Banana of the Youngbloods, living in West Marin at the time, bought a banjo from my father.

My dad would take us over to the Grateful Dead’s house on Arroyo Road and we would swim in the pool, splashing and screaming while Bob Weir jumped off the diving board and landed in the water near us.

My father put his heart and soul into our home. He brought home a gypsy wagon that became my sister’s bedroom. He built a huge bathtub out of redwood and countless coats of resin for waterproofing. The yard was filled with his sculptures (artwork which the neighbors considered junk!) and all kinds of stuff he found on his travels around the Bay Area and dragged home to add to his future-art pile.

The light in his woodshop (his sanctuary) always burned bright long into the night. This was the happiest time of my life. I wandered all over the hills, a tomboy, and my sister and I played among the Manzanita trees. Using the lichen growing on them, we made houses and clothes for our Barbies and troll dolls.

The three of us kids shared a room, my sister lording it over us in her single bed, and my brother and I sharing bunk beds. Knowing beyond a doubt that monsters were hiding in the darkness beneath my bed waiting for me, I would run from the doorway of the bedroom and leap into the lower bed, taking careful aim so as not to smack my head on the upper bed.

Susu, my precious cat, gave birth to her squirming litters of kittens in my bed. My mom wasn’t too happy about that but I was ecstatic.

The school bus picked us up next to Cliff’s Grocery Store, a quarter mile down the hill on Sir Francis Drake Boulevard, the main road in the Valley. Wandering down to the bus stop every morning wasn’t too bad; we usually had plenty of time to catch the bus. It was having to drag ourselves all the way back up the hill after a long school day that I objected to, and I would beg my mom to drive us to school and pick us up. It hardly ever happened.

Now, suddenly, my family is homeless. Our home, bought for us in 1963 by our beloved grandparents, is lost, forever. I didn’t understand it then, I found out many years later that the house had gone into foreclosure proceedings after my grandparents stopped paying the mortgage and didn’t tell my mother. She received the notice of foreclosure two days before Christmas, 1968. Six days before my twelfth birthday.

We are to be sheltered by friends, by strangers who sometimes become friends and by friends who turn into strangers; we also seek refuge amongst strangers who just remain strange. We finally come to an uneasy rest at the scattered homes of Peter Coyote’s commune, a loose tribe of people known as “The Family.”

We, the children, do not realize, in the darkness of the car, just how our lives have changed. Sitting in the backseat, wedged together among our belongings, we don’t understand what was happening to us, or why.

There is no more normal, everything is viewed through a prism of “before” versus “now.” There would be no more school for us two oldest - the daughters. I would have no more schoolyard friendships, or awkward but happy-to-be-included sleepovers.

There are, also, no more dentist visits, no more doctor visits, and the clothes we wear come from “free boxes.” We learn to do without. Uncertainty and change are the constants. There are times when we don’t know if we would eat at night. There are times when we don’t eat.

My father had made some mistakes, and his young family was paying the price. We had no idea what those mistakes were at the time, how could we know that what he had done was wrong? My father was unquestionably right about everything, wasn’t he? Even when Travis, the young sheriff, came to question me, a 9 year old, about whether I would have slashed tires on our road, how was I to know this was harassment of my father? Travis had it out for my father, he wanted to clean the Valley of the hippie element and would stoop to interrogating a child in his efforts to intimidate.

Even after I was old enough to know the truth, I did not have the capacity to judge him. When he didn’t come home for days on end, I just missed him terribly. The senior sheriff waited, parked on the road outside our home until I came home from visiting friends, forced his way in to search our dark, empty house for my father, as I stood trembling and scared with the comforting arms of my friend’s mother around me. Even when we went to visit him in the Marin County jail, separated by a thick glass panel, I was just bewildered but accepting, never angry or judgmental.

My fragile mother paid a price for my father’s mistakes as well. Unfortunately this was a price that we could not afford. Her madness took her so far away from us, to a place where no one could reach her, and it began that night in the car as she watched her world collapse. She has never fully returned; not too many years later she and I switched roles and even today she is still dependent upon me for her survival.

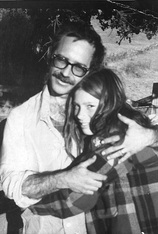

My father was not a stupid man. Although his high school refused to divulge his scores back then, I’ve been told that was because his IQ was so much higher than the other kids, he was on the genius level. My father wanted to create a life of art, beauty, music, poetry and love. A rebel from early on, he lived on the edges of societal norms, and he truly, deeply, believed that art is life, life is art. He had a restless intellect. He was infinitely curious and not satisfied with the way things were. His friends were musicians, artists, free-thinkers, intellectuals, and radicals. His wife, the mother of his children, wasn’t always comfortable with his radical way of thinking, however, she was especially alarmed with his interest in the philosophy of the Summerhill School in England – where children are free to choose what to do with their time, based on the founder Alexander Neill’s belief that ‘the function of a child is to live his own life…” But they both raised us, at least in the early years, with love and pride.

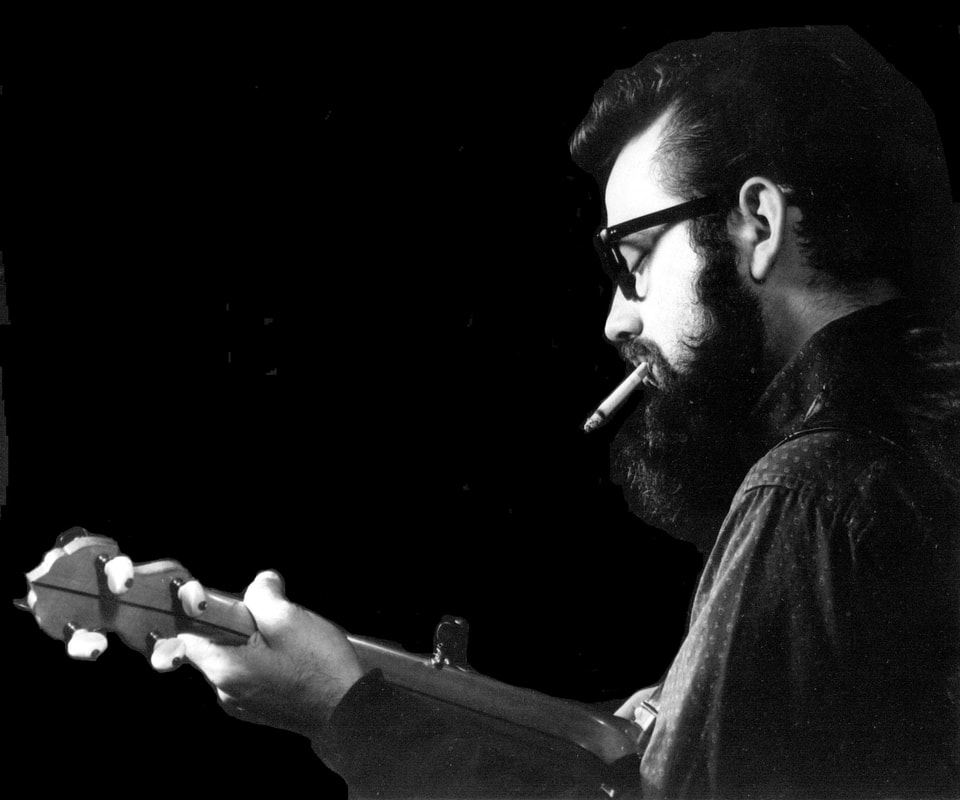

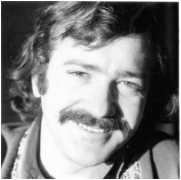

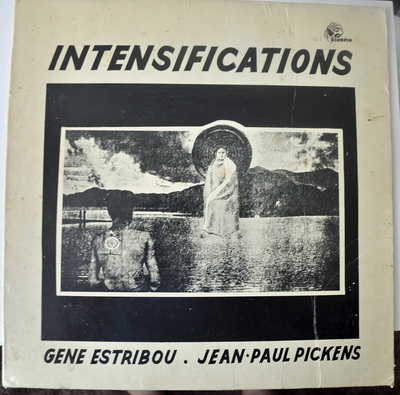

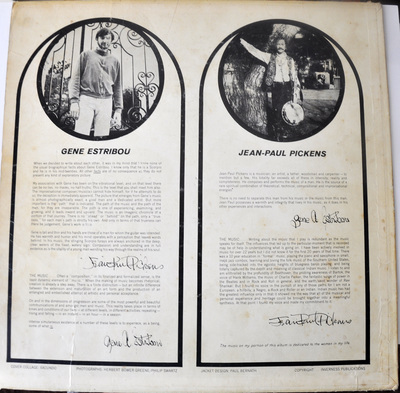

My father lived, breathed and composed music, endlessly. He loved the joy of creating it. He was trained on the piano and guitar, but he chose the banjo because that best expressed the music he felt in his heart. I would come home, walking wearily up the hill after school, and I could hear him playing as I neared the house. He would be sitting in his woodshop or in a chair in front of the house, playing his heart out. The sounds he was making expressed his joy in life and it would make me so happy to hear it. I felt safe and comfortable - his music made the world okay for me.

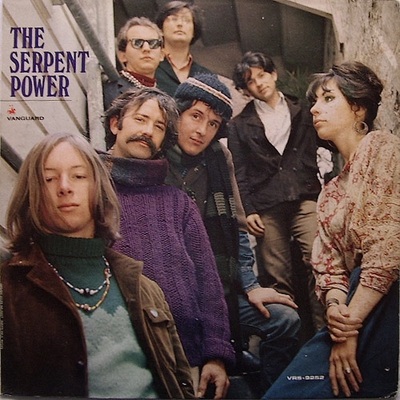

In the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, folk music was the politically correct music of the day, but he and his friend David Meltzer listened deeply, for hours, days and months on end, to all music available on LPs: blues, jazz, gospel, country, bluegrass. The New Lost City Ramblers, Django Reinhardt, Charlie Parker, Flatt and Scruggs, Ravi Shankar; David and my father collected hundreds of records and listened to them all. During their improvisational sessions they strove to recombine all the sounds they had heard. Most folkies disdained their attempts, with the exception of some of the musicians who went on to form the seminal bands of the early psychedelic rock scene of San Francisco: Jim Gurley, Dino Valenti and David Crosby. David Meltzer and my father played their unique music at the Coffee Gallery in North Beach, San Francisco, in the early 1960s, unsettling the hootenanny crowd but exciting the hipsters. Janis Joplin sang with them, during her first trip to San Francisco from Texas. Jim Gurley accompanied them, and the music they played at the Coffee Gallery shaped and defined the musical style, psychedelic rock, that would later sweep the nation.

When it became urgent for me to learn more of the person my father had been and to try to understand why he made the choices he did, I reached out to David Meltzer, to fill in some of the blanks. He shared these stories about my dad with me, a friend he grieves for to this day, and along the way helped me put my life into perspective.

Drugs have been used by musicians and artists for decades, and my father and his friends were not exceptions. Marijuana was the most common drug, and smoking it was considered to be a harmless recreational high, shared among friends and strengthening creative bonds.

The first time my father tried methedrine, however, he said that he “saw the face of God, and the Universe opened up” to him. His awareness expanded to “touch the farthest reaches of space” and he thought he had found “the answer to life, to higher creativity and productivity.” His use of methedrine was casual at first, to “add fuel to creating art and music.” His banjo playing, already legendary for his lightning fast fingerpicking, picked up in tempo.

In early 1968, a friend and fellow user in the Valley betrayed my father to the police, in order to reduce his own jail time for a prior bust. This “friend” helped an undercover cop entrap my dad with a marijuana buy. Jail was a brutalizing experience for my artistic, creative and sensitive father. It seared his soul. Once released, methedrine offered comfort and escape.

He missed court dates. My sister remembers his mood swings would be radical, some days he would be happy and playing music or working in his woodshop, and other days his mood would be darker than dark. He would be gone from the house for days, sometimes weeks, at a time. My mom, I realize looking back, became depressed and would stay in bed for days. The house became messier, and the over-full yard alarmed the neighbors. The last time I spoke with my father’s sister, in the fall of 2007, she told me that in 1968 the sheriff had called my grandparents and threatened to arrest them (they were the title-holders on the house) because the house and yard were health-hazards. Since much of what she said to me during this shockingly anger-and-hate-filled rant on the telephone later proved to be lies, I don’t put any belief in this.

My sister, brother and I were pretty much on our own. Sometimes young women would show up at our door, sent by my father from the hippie houses he visited in San Francisco, to cook, clean and take care of us. We grew attached to one of these young women and we nicknamed her Mary Poppins, followed her around like puppies and happily ate her vegetarian meals.

In summer of 1968, the children’s beloved grandparents came up from San Diego, along with the sister and her attorney husband, to plead with him to enter a mental institution. To them, his behavior could not be anything other than sheer madness, insanity. He refused.

My father thought he could control the drug, and the drug destroyed him. After we moved from our home in Lagunitas I rarely saw him. He spun off into a world I could not imagine, inhabiting a surreal netherworld of drugs, low-life characters and lost opportunities. I know it was not a world he would have chosen. With his intellect and his musical talent he could have been one of the stars of the psychedelic rock era, but the twists and turns of fate and fortune placed him into this particular hell.

As David Meltzer wrote about my father, “…We realize our prison only after we design it and move in.”

In the end, my father lost so much that was dear to him: first his home; then his cherished parents and sister who could not understand him. Finally, two months and two days after his thirty-sixth birthday, his life. I believe that his heart was broken by those he trusted, whether that trust was well-placed or not – drug users, hippie friends, and his family – and he lost his will to survive.

His only son, named after his father, also died, two months and nine days after his own thirty-sixth birthday. I often wonder if Paul would be alive today if he had been allowed to stay with my father’s sister when he was twelve. Never able to defeat the demons few knew about, Paul struggled for years with an addiction to drugs, and finally gained sobriety nine months before his death from AIDS. Paul lived every minute of his last years with gratitude and love, and he bore the unknowable pain and indignities of a fatal illness with grace, courage and strength.

My mother is fragile still, and unable to understand, or take responsibility for, the choices she made as a young mother that left her children vulnerable.

His daughters, my sister and I, survived. We have finally learned, although we paid such a high price, to live our lives with joy, strength, dignity and intelligence. I founded a nonprofit organization, named after my brother, and my husband and I travel the world promoting the mission of the organization: to improve health and elevate consciousness worldwide. KayAnne has built a good life for herself as an artist, living with her husband in the mountains of Colorado.

Although I never spoke with my father’s sister again after the toxic phone call in the fall of 2007, I have learned so much about her since then. She was still so angry, decades after my father died, that her parents had “never denied him anything, he never lifted a finger to help them” and she “was forced to do it all, they bought a washing machine, and then a house, for him” and they never bought her a thing, “she had to work hard for anything” she wanted. And although I found out (much too late) that my grandparents had left us an inheritance, I came to understand that although I had loved her blindly because she was my connection to the father I lost, I actually never knew her. This became so clear during the lawsuit my sister and I filed against her to try to claim our inheritance. In the summer of 2007, out of the blue, I started wondering if my grandfather had left a will. Following my intuition I went searching to see if I could find if a will was filed after he died in 1993. Quite easily, I found my grandfather’s will in the Probate Court of San Diego, and as I sat there reading through it, I was stunned to find that his son’s children were named as beneficiaries. Our grandparents did love us, and did consider us family! .

I would have loved to ask my father’s sister, the woman formerly known as my aunt, a couple of questions.

Were you the one who convinced my grandparents to stop paying the mortgage in late 1968 on the house they bought for their only son and his young family...

and not tell my mom?

From 2015:

I have a story to tell you. This is a story about a young family, leaving behind everything familiar and setting out on a harrowing journey, which forever altered the course of their lives. The year is 1969. The young father and mother, both 33 years old, have three children ranging in ages between nine and thirteen years old. They travel in their car up a one-lane dirt road, at night. It is mid spring, and still cold outside. The car is a station wagon, and the father is driving. The mother is sitting next to him and the three children are sitting in the back seat. The car is crunching over rocks, sticks and leaves as it travels up the road, heading toward a house full of strangers and a life of uncertainty.

The car is packed with blankets, clothes, and the few personal belongings they could fit. The middle child is 12, that’s me, Cheryl Lynne, painfully shy but sharply observant, mostly over-looked because I don’t make a fuss. My sister, Kay Anne, is 13 years old, she’s the extrovert, reveling in the attention she demands. Our brother, Paul, the adored baby of the family, is nine.

My grandfather nicknamed Paul ‘Boy.’ Rushing onto the plane after it landed in Los Angeles from Portland, Oregon, to grab his newborn grandson, his namesake, from my mother’s arms, shouting, “That’s my Boy! That’s my Boy!” My grandparents were from Texas, where family is everything, the only thing worth value. And it was my brother only, in 1972, that my father’s sister brought into her home; she cut his hair, bought him new clothes and enrolled him in a nearby school. After six months, my frantic mother ‘rescued’ her son from this home.

Our car is heading away from our home, away from the known and the beloved. The house had been packed up, some stuff thrown away, more stuff given away, and what couldn’t be parted with is stored in friends’ garages in the valley. Over the years, these belongings, like so much else, would disappear.

The headlights shine up into the darkness, showing the road and bathing the trunks of the trees lining the road in light. My father is telling jokes, laughing, singing, and trying to cheer up his stunned children. Suddenly my mother turns to the back and snaps at us, “Can’t you see how hard this is on your father?”

Good god, what? Was she kidding? I felt the shock go deep into my body, and bewildered by her anger I waited, but my father went silent. His silence was more disturbing to me than her angry outburst, for I had never known him to be at a loss for words.

The car continues climbing up to the top of the ridge, to the unfamiliar house, where my family will stay for a few weeks. This will be the first stop in a long line of other strange houses where we will stay for a few weeks, maybe a few months. I have no idea where we are going as we grind slowly up the road, just a vague notion of “staying with friends for a little while.” My father parks the car and we go inside with our small bags, the otherness of the place and the strangeness of the people make me hang back.

Our house, our home, nestled in the hills of Lagunitas and perched at the top of a small, winding road, had always been filled with love, books, and music. Famous musicians - Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead, John Cippolina and Jim Murray of the Quicksilver Messenger Service, Michael Bloomfield and many others - were always dropping by to jam with my father. Banana of the Youngbloods, living in West Marin at the time, bought a banjo from my father.

My dad would take us over to the Grateful Dead’s house on Arroyo Road and we would swim in the pool, splashing and screaming while Bob Weir jumped off the diving board and landed in the water near us.

My father put his heart and soul into our home. He brought home a gypsy wagon that became my sister’s bedroom. He built a huge bathtub out of redwood and countless coats of resin for waterproofing. The yard was filled with his sculptures (artwork which the neighbors considered junk!) and all kinds of stuff he found on his travels around the Bay Area and dragged home to add to his future-art pile.

The light in his woodshop (his sanctuary) always burned bright long into the night. This was the happiest time of my life. I wandered all over the hills, a tomboy, and my sister and I played among the Manzanita trees. Using the lichen growing on them, we made houses and clothes for our Barbies and troll dolls.

The three of us kids shared a room, my sister lording it over us in her single bed, and my brother and I sharing bunk beds. Knowing beyond a doubt that monsters were hiding in the darkness beneath my bed waiting for me, I would run from the doorway of the bedroom and leap into the lower bed, taking careful aim so as not to smack my head on the upper bed.

Susu, my precious cat, gave birth to her squirming litters of kittens in my bed. My mom wasn’t too happy about that but I was ecstatic.

The school bus picked us up next to Cliff’s Grocery Store, a quarter mile down the hill on Sir Francis Drake Boulevard, the main road in the Valley. Wandering down to the bus stop every morning wasn’t too bad; we usually had plenty of time to catch the bus. It was having to drag ourselves all the way back up the hill after a long school day that I objected to, and I would beg my mom to drive us to school and pick us up. It hardly ever happened.

Now, suddenly, my family is homeless. Our home, bought for us in 1963 by our beloved grandparents, is lost, forever. I didn’t understand it then, I found out many years later that the house had gone into foreclosure proceedings after my grandparents stopped paying the mortgage and didn’t tell my mother. She received the notice of foreclosure two days before Christmas, 1968. Six days before my twelfth birthday.

We are to be sheltered by friends, by strangers who sometimes become friends and by friends who turn into strangers; we also seek refuge amongst strangers who just remain strange. We finally come to an uneasy rest at the scattered homes of Peter Coyote’s commune, a loose tribe of people known as “The Family.”

We, the children, do not realize, in the darkness of the car, just how our lives have changed. Sitting in the backseat, wedged together among our belongings, we don’t understand what was happening to us, or why.

There is no more normal, everything is viewed through a prism of “before” versus “now.” There would be no more school for us two oldest - the daughters. I would have no more schoolyard friendships, or awkward but happy-to-be-included sleepovers.

There are, also, no more dentist visits, no more doctor visits, and the clothes we wear come from “free boxes.” We learn to do without. Uncertainty and change are the constants. There are times when we don’t know if we would eat at night. There are times when we don’t eat.

My father had made some mistakes, and his young family was paying the price. We had no idea what those mistakes were at the time, how could we know that what he had done was wrong? My father was unquestionably right about everything, wasn’t he? Even when Travis, the young sheriff, came to question me, a 9 year old, about whether I would have slashed tires on our road, how was I to know this was harassment of my father? Travis had it out for my father, he wanted to clean the Valley of the hippie element and would stoop to interrogating a child in his efforts to intimidate.

Even after I was old enough to know the truth, I did not have the capacity to judge him. When he didn’t come home for days on end, I just missed him terribly. The senior sheriff waited, parked on the road outside our home until I came home from visiting friends, forced his way in to search our dark, empty house for my father, as I stood trembling and scared with the comforting arms of my friend’s mother around me. Even when we went to visit him in the Marin County jail, separated by a thick glass panel, I was just bewildered but accepting, never angry or judgmental.

My fragile mother paid a price for my father’s mistakes as well. Unfortunately this was a price that we could not afford. Her madness took her so far away from us, to a place where no one could reach her, and it began that night in the car as she watched her world collapse. She has never fully returned; not too many years later she and I switched roles and even today she is still dependent upon me for her survival.

My father was not a stupid man. Although his high school refused to divulge his scores back then, I’ve been told that was because his IQ was so much higher than the other kids, he was on the genius level. My father wanted to create a life of art, beauty, music, poetry and love. A rebel from early on, he lived on the edges of societal norms, and he truly, deeply, believed that art is life, life is art. He had a restless intellect. He was infinitely curious and not satisfied with the way things were. His friends were musicians, artists, free-thinkers, intellectuals, and radicals. His wife, the mother of his children, wasn’t always comfortable with his radical way of thinking, however, she was especially alarmed with his interest in the philosophy of the Summerhill School in England – where children are free to choose what to do with their time, based on the founder Alexander Neill’s belief that ‘the function of a child is to live his own life…” But they both raised us, at least in the early years, with love and pride.

My father lived, breathed and composed music, endlessly. He loved the joy of creating it. He was trained on the piano and guitar, but he chose the banjo because that best expressed the music he felt in his heart. I would come home, walking wearily up the hill after school, and I could hear him playing as I neared the house. He would be sitting in his woodshop or in a chair in front of the house, playing his heart out. The sounds he was making expressed his joy in life and it would make me so happy to hear it. I felt safe and comfortable - his music made the world okay for me.

In the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, folk music was the politically correct music of the day, but he and his friend David Meltzer listened deeply, for hours, days and months on end, to all music available on LPs: blues, jazz, gospel, country, bluegrass. The New Lost City Ramblers, Django Reinhardt, Charlie Parker, Flatt and Scruggs, Ravi Shankar; David and my father collected hundreds of records and listened to them all. During their improvisational sessions they strove to recombine all the sounds they had heard. Most folkies disdained their attempts, with the exception of some of the musicians who went on to form the seminal bands of the early psychedelic rock scene of San Francisco: Jim Gurley, Dino Valenti and David Crosby. David Meltzer and my father played their unique music at the Coffee Gallery in North Beach, San Francisco, in the early 1960s, unsettling the hootenanny crowd but exciting the hipsters. Janis Joplin sang with them, during her first trip to San Francisco from Texas. Jim Gurley accompanied them, and the music they played at the Coffee Gallery shaped and defined the musical style, psychedelic rock, that would later sweep the nation.

When it became urgent for me to learn more of the person my father had been and to try to understand why he made the choices he did, I reached out to David Meltzer, to fill in some of the blanks. He shared these stories about my dad with me, a friend he grieves for to this day, and along the way helped me put my life into perspective.

Drugs have been used by musicians and artists for decades, and my father and his friends were not exceptions. Marijuana was the most common drug, and smoking it was considered to be a harmless recreational high, shared among friends and strengthening creative bonds.

The first time my father tried methedrine, however, he said that he “saw the face of God, and the Universe opened up” to him. His awareness expanded to “touch the farthest reaches of space” and he thought he had found “the answer to life, to higher creativity and productivity.” His use of methedrine was casual at first, to “add fuel to creating art and music.” His banjo playing, already legendary for his lightning fast fingerpicking, picked up in tempo.

In early 1968, a friend and fellow user in the Valley betrayed my father to the police, in order to reduce his own jail time for a prior bust. This “friend” helped an undercover cop entrap my dad with a marijuana buy. Jail was a brutalizing experience for my artistic, creative and sensitive father. It seared his soul. Once released, methedrine offered comfort and escape.

He missed court dates. My sister remembers his mood swings would be radical, some days he would be happy and playing music or working in his woodshop, and other days his mood would be darker than dark. He would be gone from the house for days, sometimes weeks, at a time. My mom, I realize looking back, became depressed and would stay in bed for days. The house became messier, and the over-full yard alarmed the neighbors. The last time I spoke with my father’s sister, in the fall of 2007, she told me that in 1968 the sheriff had called my grandparents and threatened to arrest them (they were the title-holders on the house) because the house and yard were health-hazards. Since much of what she said to me during this shockingly anger-and-hate-filled rant on the telephone later proved to be lies, I don’t put any belief in this.

My sister, brother and I were pretty much on our own. Sometimes young women would show up at our door, sent by my father from the hippie houses he visited in San Francisco, to cook, clean and take care of us. We grew attached to one of these young women and we nicknamed her Mary Poppins, followed her around like puppies and happily ate her vegetarian meals.

In summer of 1968, the children’s beloved grandparents came up from San Diego, along with the sister and her attorney husband, to plead with him to enter a mental institution. To them, his behavior could not be anything other than sheer madness, insanity. He refused.

- I don’t know what my grandparents thought when they stopped paying the mortgage and signed the house over to my parents. I know that they did not tell my mother, and when she learned that the mortgage had not been paid for three months, and the house was in foreclosure she did not have the money to pay the overdue mortgage and save our home.

My father thought he could control the drug, and the drug destroyed him. After we moved from our home in Lagunitas I rarely saw him. He spun off into a world I could not imagine, inhabiting a surreal netherworld of drugs, low-life characters and lost opportunities. I know it was not a world he would have chosen. With his intellect and his musical talent he could have been one of the stars of the psychedelic rock era, but the twists and turns of fate and fortune placed him into this particular hell.

As David Meltzer wrote about my father, “…We realize our prison only after we design it and move in.”

In the end, my father lost so much that was dear to him: first his home; then his cherished parents and sister who could not understand him. Finally, two months and two days after his thirty-sixth birthday, his life. I believe that his heart was broken by those he trusted, whether that trust was well-placed or not – drug users, hippie friends, and his family – and he lost his will to survive.

His only son, named after his father, also died, two months and nine days after his own thirty-sixth birthday. I often wonder if Paul would be alive today if he had been allowed to stay with my father’s sister when he was twelve. Never able to defeat the demons few knew about, Paul struggled for years with an addiction to drugs, and finally gained sobriety nine months before his death from AIDS. Paul lived every minute of his last years with gratitude and love, and he bore the unknowable pain and indignities of a fatal illness with grace, courage and strength.

My mother is fragile still, and unable to understand, or take responsibility for, the choices she made as a young mother that left her children vulnerable.

His daughters, my sister and I, survived. We have finally learned, although we paid such a high price, to live our lives with joy, strength, dignity and intelligence. I founded a nonprofit organization, named after my brother, and my husband and I travel the world promoting the mission of the organization: to improve health and elevate consciousness worldwide. KayAnne has built a good life for herself as an artist, living with her husband in the mountains of Colorado.

Although I never spoke with my father’s sister again after the toxic phone call in the fall of 2007, I have learned so much about her since then. She was still so angry, decades after my father died, that her parents had “never denied him anything, he never lifted a finger to help them” and she “was forced to do it all, they bought a washing machine, and then a house, for him” and they never bought her a thing, “she had to work hard for anything” she wanted. And although I found out (much too late) that my grandparents had left us an inheritance, I came to understand that although I had loved her blindly because she was my connection to the father I lost, I actually never knew her. This became so clear during the lawsuit my sister and I filed against her to try to claim our inheritance. In the summer of 2007, out of the blue, I started wondering if my grandfather had left a will. Following my intuition I went searching to see if I could find if a will was filed after he died in 1993. Quite easily, I found my grandfather’s will in the Probate Court of San Diego, and as I sat there reading through it, I was stunned to find that his son’s children were named as beneficiaries. Our grandparents did love us, and did consider us family! .

I would have loved to ask my father’s sister, the woman formerly known as my aunt, a couple of questions.

Were you the one who convinced my grandparents to stop paying the mortgage in late 1968 on the house they bought for their only son and his young family...

and not tell my mom?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed